Project Nim

On the surface, James Marsh’s Project Nim, is about a group of people’s quest to teach a chimp sign language. And if it was just about that, it probably would have been a great documentary. But it touches on so many other, very meaningful themes—most notably, abandonment and selfishness—that one can’t help but admire the hell out of it. It’s actually the film’s human characters that ultimately come under Marsh’s microscope, and what we see isn’t pretty. It is, however, very powerful. I wasn’t as enamored as many others were with Man on Wire, Marsh’s previous feature, but Project Nim is sensational.

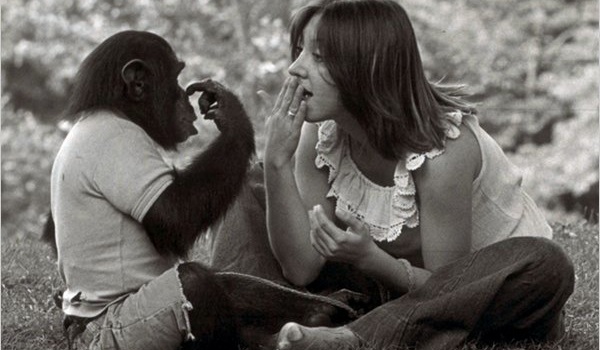

Nim Chimpsky is the name of the film’s featured primate. He was born on a reserve but moved at a very early age to a Manhattan brownstone where he was to be raised as a human child in a classic test of nature vs. nurture. The experiment’s administrator is Dr. Herb Terrace, but he stays hands-off for the most part, instead relying on several different research assistants and students to look after and raise the chimp. They begin teaching him sign language, and a great deal of progress is made (Nim dresses himself and seemingly mirrors the emotional growth of a human toddler).

Despite the obvious intelligence and self-awareness that Nim shows, he’s not entirely able to give him his natural tendencies. He bites when he doesn’t get what he wants, causing more than one caretaker to leave out of fear of getting hurt. This, in turn, causes him to be moved from his first home into a more secluded one, and ultimately from that home back to the reserve where he came from.

What’s sad is that these people can’t seem to grasp that Nim isn’t a person. He doesn’t know any better. Yes, he’s smarter than most chimps, but he proves completely unable to create a coherent sentence, nor can he express anything that isn’t a statement of want or need. Nim isn’t a conversationalist, which was ultimately what Terrace was going for. But does the chimp’s failure to comprehend mean he deserves to be completely abandoned? Of course not, yet that’s what most of those who raised him do.

Politics, money, infighting, and some twisted personal morals and boundaries ultimately stop the formal experiment and serve as the catalyst for Nim’s abandonment. Nim acts out, but not in such a way that he can’t be looked after. At his reserve, he thrives in the care of a kindly and patient hippie. But he’s visited only once by someone from his childhood—Terrace, who goes only to get pictures and video of him with the chimp. Watching Nim rejoice upon seeing him is tragic because we know how it will end. And seeing the way Terrace later writes Nim off because the experiment didn’t play out the way he wanted it to is a little sickening.

Project Nim, unlike some of the year’s other great documentaries, was shortlisted for the Academy Awards, but it was ultimately left off the final list of nominees. Marsh isn’t a big name like Errol Morris or Steve James, but he’s now made two very good-to-great documentaries in just three years. He also directed one of the Red Riding Trilogy films, and had a narrative feature (Shadow Dancer) debut to good reviews at Sundance this year starring Clive Owen and Andrea Riseborough. So in addition to being a fantastic film, Project Nim does something else: It puts all film writers on notice. Any list of the best working filmmakers (or promising up-and-comers) is incomplete without the name James Marsh on it.