The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975

If nothing else, The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 proves there is such a thing as truth in advertising. Billed as the greatest hits of some found footage filmed during the titular time period, the film really is a mixtape. But not every track on a mixtape is created equal. As such, I really dug some of what the film had to offer, but other segments left me cold and disinterested. It’s certainly one of the more interesting documentaries of 2011, but its unusual structure ends up being a point of both praise and detraction.

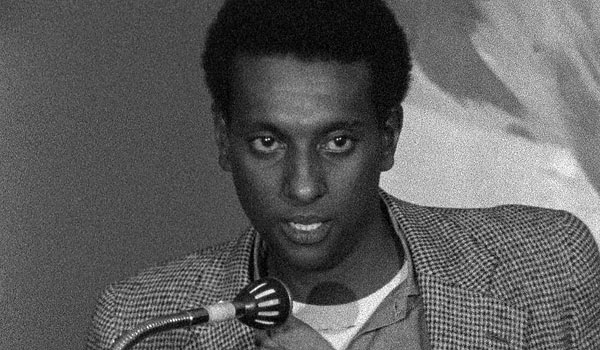

The seeds of the black power movement appear to have been planted around 1967-1968. It’s during this time that we meet Stokely Carmichael, a charismatic leader of the growing movement. During a speech in Stockholm (the film is made by a group of Swedish journalists), Carmichael presents of vision of resistance that doesn’t go so far as the ones Malcolm X and Louis Farrakhan would extoll a few years later, but it’s certainly different than Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for non-violence. And after King is killed, Carmichael’s words spread. They are picked up by a number of black activists from Oakland to Algeria, and the Black Panther Party is born.

The film gets less and less interesting the longer it goes on. I suppose that’s because, for whatever reason, the origins of black power are more compelling than the way it loses steam. Clearly, people weren’t ready for the radical change proposed by the leading thinkers of this movement. They preferred incremental or no change to an overnight systemic shakeup. That’s all good, as far as real world politics goes. As a film watcher and writer, I naturally root for conflict, and the latter years covered by the film don’t have a ton of it.

That’s not to say the film is totally without merits after 1968. The Angela Davis interview is probably the highlight of the entire film and takes place well after the new decade starts. Also attention-grabbing is the way director Göran Olsson injects opinions on his native Sweden into the film. When a TV Guide article is published stating that Sweden has the most anti-American television shows, Stockholm is thrust into the spotlight of the black power movement. “Why is giving a voice to black power considered anti-American?” interviewees argue. “Good question,” I’d respond.

Ultimately, it’s hard to say if the film’s structure serves it well or not. It’s interesting, but the end result is a film that comes across as jumbled and unfocused all too often. There’s a great documentary to be had with this found footage. This, however, is merely a good one.