That Night’s Wife Review

The words “crime drama” bring to mind shadowy characters doing dirty deals in back rooms or pool halls. Noir is token “crime drama,” and noir is awesome. But noir is not Yasujirô Ozu’s bag. His crime drama is still a Ozu film, but its inciting incident is a thrilling caper. It’s this surprising juxtaposition that defines That Night’s Wife, one of the three films in Criterion’s Eclipse Series set “Silent Ozu — Three Crime Dramas”. And while there’s much more filmmaking verve in the shorter “crime” portion of this crime drama, the tenderness that defines the the “drama” portion is worthy of Ozu and worth 75 minutes of your time.

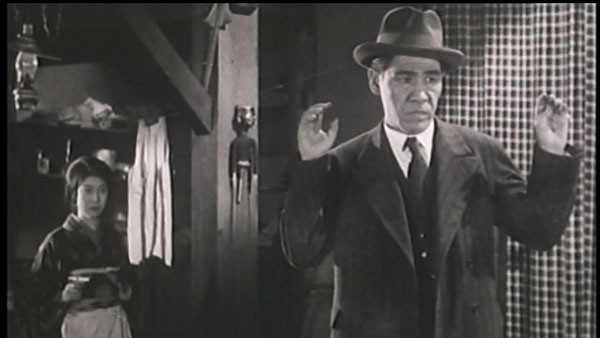

The story is basically a take on Les Miserables’ table setting. In the dead of night, a man (Tokihiko Okada) commits a crime. But malice or greed is not his motive; Instead, he’s trying to save his critically ill daughter (Tatsuo Saitô). He’s pursued aggressively by the police as he navigates the quiet streets, trying to find a safe route home. He does, but on his tail is the wily Detective Kagawa (Togo Yamamoto).

Once home, a doctor tells the man and his wife (Emiko Yagumo) that this night will decide their daughter’s fate, but so it will the man’s, as Kagawa drops in to make the arrest. Upon seeing that he’s caring for a very sick child, the detective agrees to wait it out with this family—an agreement that’s fine with the man because he feels terrible guilt over his actions.

And that’s just the start of the night. Over the course of these hours, and as this little girl’s prognosis changes, both the man and his wife (separately and together) consider ways he might be able to get out of what the morning certainly brings—arrest and imprisonment. That Night’s Wife goes a lot of places in a short amount of time, and while that occasionally makes it feel a little schizophrenic or scatter-brained, it also allows the films dilemmas to develop more naturally.

The human element of the film, however, is totally on point. Stripped bare of everything that’s not totally essential, this story is very emotionally involving. And Ozu’s style, which I’ve already stated is showiest during the film’s opening scenes, still lingers beautifully on his actors’ longing faces, conflicted conversations, or desperate movements.

Because the film is mostly confined to one set, its urgency is palpable. This plays out, too, in the film’s standout shot, which captures our protagonist in a phone booth, calling home to check in while still on the run from the police. He presses his hand up against the glass, and it shakes. Equal parts fear, shame, and adrenaline, it’s the kind of lightning-in-a-bottle shot that captures an entire film’s spirit perfectly and signifies a major f’ing talent. It’s something we don’t necessarily need to know about Yasujirô Ozu 85 years after this film’s release; We already know the kind of gargantuan creative mind we’re dealing with. But it’s nonetheless fun and rewarding to see him working on a world-class level so early in his career and in such an atypical way.