Ranking the 2015 Best Picture Nominees

It occurred to me the other day that, despite seeing every film nominated for the 2015 Best Picture Oscar, I’ve only formally reviewed one. What?!? And it was a dud of a film—The Theory of Everything.

Maybe that speaks to my general indifference toward this crop of nominees; after all, it’s easier and way more fun to write overwhelmingly positive or overwhelmingly negative reviews. But man, that was a bizarre oversight, and hopefully, this is something of a mea culpa (assuming such a thing is even necessary).

Today, I’m ranking all eight Best Picture nominees in descending order of preference and at the same time, I’m offering a number of sprawling, spoiler-filled thoughts about the quality of these films and, in some cases, the quality of discussion around them. I have some unique takes, and I hope you can appreciate and enjoy them.

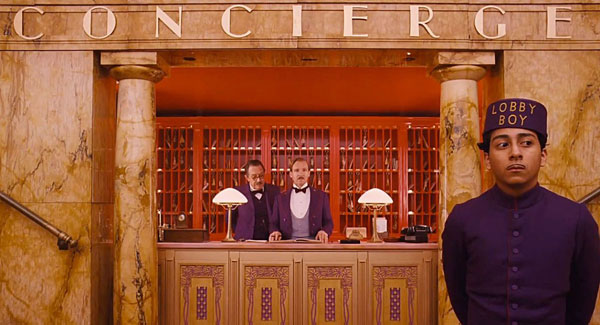

1.) The Grand Budapest Hotel

(Number of times watched: 3)

While I haven’t formally reviewed Wes Anderson’s second-best movie, I’ve still written about it a fair amount over the last few months. Wasn’t crazy about it on first glance. Fell head over heels on a rewatch, and it ended up topping my first pass at a Best Movies of 2014 list back in December.

So why does this film work so well for me? This piece by John Lopez on Grantland brings up a lot of what I love about Anderson’s films (and really, films in general). If there’s an overarching theme to the films that typically pull me in most regularly and most closely, it’s an ability to mix great levity and great sadness. It’s a really hard thing to do, but in 2014, the two Andersons—Wes and Paul Thomas—did it super successfully, and their films ended up being the two best I saw.

Inherent Vice and The Grand Budapest Hotel are both wildly romantic, but they’re romantic for and about a specific period of time more than they are for another person (though there are elements of human-to-human romanticism in both films, as well). I don’t think that explains the disconnect in the amount of Academy love between the films, though. That comes down more to the period itself and the way the stories unfold.

The Grand Budapest Hotel is one of the most unusual WWII movies ever made, and I doubt that’s lost on Academy voters. More interestingly, to me at least, is the way the films share a dream-like quality that manifests itself differently between the two films, and the way it does that feels unique to each filmmaker. (Interstellar does this to a degree, as well, and in service of a similiar theme, that is fear of losing a certain way of life.) The Grand Budapest Hotel really is a dream. When you’re talking about a memory within a memory within a memory—it’s a film about a girl who remembers an author who tells the story of a man whose life was changed as a much younger man by the star of the film—the line between fact and fiction blurs. Nevermind that one of those links is a writer, a professional storyteller, and one wonders if, in this world’s reality, we’re getting the whole truth, etc.

But ultimately, it’s not the dream Inherent Vice is. It’s easier to digest with its perfectly framed images and straight-razor camera movements. It’s a mom’s shoebox diorama compared to PTA’s Pollock, which sounds insulting but isn’t meant to be. It’s just warmer and fuzzier than the film it shares a sense of melancholy with, and as such, it’s rather obvious why the Academy embraced Grand Budapest over Inherent Vice, despite a bizarre lack of recognition for the Hotel‘s conceirege, a rarely better Ralph Fiennes. I’m a little surprised either became a nominations-leading consensus movie, but if either did, it was always The Grand Budapest Hotel.

2.) Whiplash

(Number of times watched: 1)

Whiplash is the most meta movie of the eight 2015 Best Picture nominees.

It’s about a college-aged man who drives himself crazy to be perfect at his craft—filmmaker much? But his craft is jazz percussion—something defined by a lack of definition. Is there such a thing as right or wrong with what Miles Teller’s Andrew wants to do creatively? Probably not, but don’t tell that to his instructor/conductor Terence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons) who will throw a chair across the room at Andrew or anyone else who’s 1/16 of a beat ahead or behind.

It’s a weird thing—a jazz instructor so rigid. But it’s not inconceivable … right?

Ultimately, the film as a whole overcomes its screenplay’s flat notes—the inconsistencies and contrivances that remind you that you’re watching a movie—without making you want to throw a cymbal across the room at someone’s head. And it kind of does so while embracing those meta-ish moments that take you out of the film. It’s a more complex film-watching experience than you’d expect, and I love it.

Whiplash is a unique take on the “What is reality?” subgenre of films that also includes The Matrix and Inception. Andrew isn’t an unreliable narrator per se, but we ride the ebbs and flows of his relationship with Fletcher, which ebbs and flows faster than a heart rate monitor. In that respect, it’s never clear if what Fletcher is doing is helping Andrew or hurting him, nor is it clear whether his actions are meant to help or hurt Andrew. A conversation between the two (might) reveal that Fletcher wants his students to achieve brilliance and that his abuse is meant to push them past a point where they doubt themselves. Andrew smartly asks if that abuse might discourage brilliant young musicians from realizing their potential. Neither is right, neither is wrong (at least in philosophy).

Andrew is the film’s strongest asset, as he’s someone we can relate to—the way he pines to be great is universal—but feel extremely detached from at the same time. He’s narrow-minded, both in terms of his goal and the way he relates to others in his life. He disposes of relationships that will get in his way, and he’s either too young or too willfully ignorant to realize that he and Fletcher are not opposing forces. One (Fletcher) demands perfection from others in violent ways, while the other (Andrew) demands perfection from himself, which can get very bloody and very ugly.

It’s a film that lives in its editing and sound and comes from somewhere deep inside its main players. Though it’s about music, it feels like the most important thing that’s happened ever. It burrowed its way deep inside me, and it’ll probably do the same to you, too.

3.) Selma

(Number of times watched: 2)

On this list, there are four overt biopics (and one biopic disguised as an original movie). Three of the four biopics, plus the half-biopic, feel content to tell a guy’s story and quietly shuffle off. Not Selma. It tells a guy’s story before dropping the mic, and you’re like “Whoa.” It’s a film that commands your attention without calling attention to itself. I don’t know how Ava DuVernay did it, but I’m sure David Oyelowo’s presence helps.

His is the best male performance of 2014, and he’s not in the running for Best Actor in favor of cute white British boy #1, cute white British boy #2, guy who bulked up, and guy with fake nose. That’s unnecessarily reductive, but that’s the state of the Best Actor race, in my opinion. The voters fucked up. This is a towering performance by a man playing a real-life hero. Instead, we awarded the guy playing the heroic Chris Kyle. Ultimately, doling out acting nominations does, in some part, come down the way a character resonates, and Chris Kyle struck more of a chord with Oscar voters than Martin Luther King, Jr. did. Interesting.

But back to Selma, which is simply the bee’s knees of biopics. It goes out of its way to bring the myth of its subject down a few pegs. What other biopic—from last year or any other—wants you to think of its subject as a smaller person after watching it than you did before watching it? That’s Selma—a movie about pauses and indecision and mistakes. A true legend and a man with few equals in American history eats breakfast with his friends, contemplatively writes his speeches, and tries to rebuild his family after indescretions come to light.

On that note, the LBJ stuff is nonsense; If you come away from Selma thinking, “Boy, I feel back for LBJ here,” you’re doing it wrong. (It = life.) This is a minor point—a way to get from point A to point B with several characters, and I don’t begrudge DuVernay that sort of creative license. (I do wish it was handled better by Paramount, which sort of absorbed the blows thinking they’d stop. They didn’t.)

I think Bradford Young, the film’s cinematographer, is a genius. The way Selma is lit is one of the most underrated features of any film from last year, and he deserved recognition from Oscar, along with the film’s costume designer, editor, and writers. It’s a real blemish on the race, this film’s general neglect. I don’t normally get upset about this kind of stuff, but in a year with so many stuffy, dull films straight up dominating these races, the lack of Selma love is a real shame—one we’ll remember for a while, one that will sting for a while.

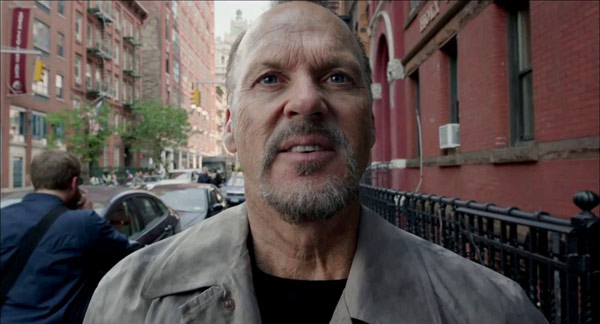

4.) Birdman

(Number of times watched: 1)

Of all the films on this list, here’s the one I’m least sure about. I left Birdman feeling frustrated because I know there’s a great movie in there somewhere. Despite what some who don’t direct movies would say, Inarritu has talent and, more importantly, something to say. His message comes across loudly and clearly in Birdman, but that’s in spite of a lot of other big and loud things screaming for your attention around the periphery of the film. In other words, I was into Birdman, so why was its director trying so hard to take me out of it?

The biggest offender is Antonio Sanchez’s drum score. It’s objectively great music outside of this world, but inside, it’s a major distraction. Birdman‘s (spectacular) cinematography tells a story defined by intense control, or at least the illusion of intense control, and that’s echoed by the actors and script. Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton, fantastic) has a death grip over this stage production when the film opens, but chance, his own neuroses, and a crazy Edward Norton start tearing down everything he’s built. So with such obsessive characters and a clearly thought-out way to frame their story, why go so fast, loose, and loud with your score? “Distracting” puts it mildly.

And worse: Why vacillate between diegetic and non-diegetic? It’s as if Inarritu can’t go more than ten minutes without gleefully reminding you that you’re watching a great movie of his by showing his drummer drumming onscreen. He simply makes too many self-congratulatory choices that left me scratching my head and grumbling to myself because for every awful nod to Sanchez there’s a scene like Riggan’s venom-laced takedown of the theater critic in the bar, which is juicy and delicious.

But Inarritu does eventually jettison all the nonsense and lets Birdman, ahem, spread its wings. How light and airy is this film after Norton disappears? (And it’s weird because Norton is GREAT.) I loved Birdman‘s last 20-30 minutes and wish it kept going in that vein. But it ends, and one-third of a great movie doesn’t make a great movie; it might make a Best Picture winner though. And of the realistic contenders on Sunday, it’s my horse.

At this point, it’s worth mentioning that I’m not easily offended. Not usually. But half—HALF!—of this year’s Best Picture nominees really bothered me on some level.

5.) American Sniper

(Number of times watched: 1)

This film opens with just sound: an Islamic call to prayer. Then, the first thing you see is a roaming tank, shot up close and from the ground up. It’s an imposing image that feels like it’s coming for that sound—to squash it and silence it.

That’s American Sniper‘s first 90 seconds. Do you think it accurately reflects the movie that follows? I’m genuinely asking because I’m still not sure. Well, I’m pretty sure, but I’m uncertain just how hawkish director Clint Eastwood really wants his film to be.

American Sniper, of all the Best Picture nominees, is the freshest with me (I only saw it this week), and while I have lots of problems with it as a character study and a piece of square-jawed American moralism, I’m intrigued by its representation of faith.

A few minutes into the film, we see a young Chris Kyle at church with his family. Their pastor is reading a passage from the Book of Acts and talking about standing in judgment for what you believe. What’s interesting about that particular section of the Bible is that it talks a lot about the history of the spread of Christianity. There are conversions and, ultimately, Paul is imprisoned in Rome for two years.

What does all this mean? I took it as a sort of defensive position—that Kyle is willing to go down swinging for what he believes. Does Eastwood know there’d be a lot of people against this film, against this character? And if so, why didn’t he want to go down a more ambiguous road with Kyle?

Honestly, knowing it’s an Eastwood movie, I’m probably reading too deeply into the minor details, but what I do feel comfortable saying today is that it’s nice to have Eastwood working on something contemporary and important. Say what you will about American Sniper, its artistic merits, and its moral implications, but it’s an important movie about an important time and a relatively minor but still important historical figure.

6.) The Imitation Game

(Number of times watched: 1)

“Don’t hate me because I’m nominated.”

That was all I could muster regarding Morten Tyldum’s The Imitation Game immediately following my one and only viewing of the film, which occurred just a couple days before the Oscar nominations were announced. It seemed like “that” film—the one that’s competently made and crowd-pleasing, but ultimately pretty uninspired; the one that people like well enough until it earns a ton of Oscar nominations and suddenly it’s the worst thing ever committed to celluloid to grace the silver screen in years, and its director should be on trial for war crimes for having the nerve to, I don’t know, receive a pat on the back from his peers.

It never really did become that film. I mean, plenty of people disagreed vehemently with first Tyldum’s DGA nomination and secondly his and his film’s Best Picture/Best Director Oscar twofer. But “Phase Two” never took off for the Alan Turing biopic, and ultimately, it was easier to forget The Imitation Game than it was to hate it.

Ironically, it was during that period of time that I figured out why people got so worked up about The Imitation Game. (I still don’t get the hate for Tyldum … his direction is ordinary and sometimes silly, but it’s inoffensive, right?) The film’s glaring problem for me was actually (nominated) lead actor Benedict Cumberbatch. I’m saying what a lot of people don’t want to: He’s not a very good actor. Sherlock is one thing, but name the man’s best performance in a feature film. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy? Probably, and he’s that film’s bronze medalist at best.

Anyway, Cumberbatch’s Aspbergers-tinged take on the genius, who according to Graham Moore’s script both ended WWII and invented computer science, is awfully affected. He never goes there—to the root of what made Turing such a tragic figure. That was my gripe with an otherwise fine-I-guess motion picture.

But Cumberbatch isn’t the problem. Not really. He’s a product of either a problematic script or a problematic film that whitewashes a good script. I’m not sure which.

The Imitation Game asks an incapable actor to be both the smartest person in the room and a sympathetic outsider. No one realizes that the “flawed genius” middle ground Cumberbatch and the film claim as their own is pretty crude. There’s nothing “flawed” about social awkwardness that stems from one’s closeted sexuality, which in turn stems from the law of 1940s Great Britain. Gayness is physically manifested as a facial spasm of sorts, and it’s he, Turing, who needs to assimilate and learn how to get on with others. It’s not until he “becomes normal” that he’s able to realize his full potential and crack his code.

And maybe that’s the way it happened in real life—that Turing marries his friend Joan and is accepted by his fellow code-crackers and shortly thereafter breaks the Nazi’s Enigma. But The Imitation Game owes its subject a more graceful telling of his story.

“Honor the man,” its Oscar campaign asked us. Voters would be best served to do so by rejecting this too-insulting take on Turing’s life.

7.) Boyhood

(Number of times watched: 2)

This one’s tough because I love Richard Linklater. I think the Before films are a towering cinematic achievement, and the rest of his filmography is littered with all kinds of sweet treats (School of Rock, Dazed and Confused, Waking Life). But Boyhood is kind of a dud and probably the most irresponsible—due to some combination of its creator’s self-indulgence and narrow world view—of the 2015 Best Picture nominees. I’ll explain.

#OscarsSoWhite was a thing this year …

Wait, I’m guessing that’s all you need me to write to know where I’m going with this. Yes, the Hispanic worker scene. It’s bad, folks—like, ruin-a-film-bad. For the uninitiated, the only person of color in the entire Texas-set film is a Hispanic worker (played by Roland Ruiz) who’s helping install piping oustside the home of the protagonist’s mother (Patricia Arquette). She tells him that he is smart and should get an education. Years later, this family is out to dinner, and the children—now young adults—are arguing with their mother. Conveniently, the aforementioned Hispanic man comes over to their table and tells the family that the mother changed his life. He’s now the restaurant’s manager, and he owes it all to that conversation in their yard.

I’ve watched Boyhood twice now. I actually dug it the first time through, but this cringe-worthy and totally pointless subplot still stuck out like a sore thumb. Viewed subsequently, in the wake of Ferguson and the host of other racial issues that plagued the fall of last year AND knowing that scene was coming, Boyhood‘s color problem became unforgivable.

And I beat this drum pretty hard around the turn of the year. In all the hubbub over “the whitest Oscars you know,” Boyhood seemed to be getting a free pass because it’s everyone’s favorite. And it’s weird because Boyhood is one of the only “original” films in the race, and where it would be odd (not unwelcome, but odd) for Morten Tyldum, James Marsh, or Clint Eastwood to revise history or the lives of real people for diversity’s sake, Boyhood seems like the film in the Oscar race that could have been color-agnostic most easily.

But something weird happened just this week—the pendulum swung so far in the other direction that I feel an obligation to defend Boyhood. An article on LatinoRebels.com—one I found mostly thoughtful if a little extreme and of questionable timing—says everything I’ve been trying to say but a little harder. Where I want to discuss with care and reason Boyhood‘s and Richard Linklater’s social responsibility to weave people of color into his film’s narrative—one that purports either explicitly or contextually, I can’t tell anymore, to be representative of the entire human experience—that article and many people on the internet this week want to call the film racist and compare it to Griffith’s Birth of a Nation.

It’s not fun searching for middle ground, but it’s also probably the most likely explanation for Boyhood‘s lack of diversity. I don’t think Linklater willfully said, “Let’s only put white people in my next movie … What, no good? OK, how about one Hispanic guy? Yeah? Great, just make sure he’s saved by some white folks. K, bye.” I think he very closely replicated life in his neck of the woods, even going so far as to cast his own daughter. This is a Linklater production, and maybe he didn’t grow up around a lot of cultural diversity. I don’t begrudge him that because I didn’t either. But it’s hard not to call a spade a spade, and Boyhood suffers because of all the things I’ve discussed here. It’s not the only thing it does wrong—that’s for another post—but it’s the biggest and most glaring error in a beloved film that very well might win Best Picture.

8.) The Theory of Everything

(Number of times watched: 1)

I mean, this one is just a turd.

I don’t hate The Theory of Everything because it’s nominated; I hate it because it’s the cinematic equivalent of salisbury steak. How anyone could get truly excited about it is beyond me, but that’s the reality we’re living in circa 2015—this British biopic without any handsome craft achievements, any unique approaches to telling a familiar story, or any above below-average performances can be named among the eight best films of a given year by a group of more than 6,000 film professionals.

But whatever. It’s not the end of the world that a crappy film got nominated for a Best Picture Oscar. It was the case last year, and the year before, and the year before, and so on. It will happen next year, and the next year, and the year after that, and so on.

What’s the film’s most egrigious misstep? The way it pussyfoots around anything resembling complicated interpersonal dynamics. It also routinely insults our intelligence by resorting to “tell it to me like I’m a five-year-old” explanations of scientific principles, but worse is the way it treats not its characters, but their relationships to each other, particularly when it comes to Stephen and Jane Hawking.

It’s not that they didn’t go there with the infidelity and his abandoning of her; instead, it’s that they handle it like Hugh Grant apologizing on The Tonight Show. “Uh, so sorry, love, but I’m afraid I’m, uh, going to have to—it’s so silly of me—leave you for the nurse, love.” The film is so concerned that we might not think Hawking is the most inspiring and wonderful human who’s ever lived that it sacrifices emotional honesty and, frankly, sells out.

Eddie Redmayne is probably going to win an Oscar for his work. He’s better—OK, maybe not, but more memorable for sure—in Jupiter Ascending. But he’s worked it for the trophy, and so has Focus for the film. I can’t tell you how many times I stumbled across a website with 12 above-the-fold images of Redmayne and Jones twirling. Ironically, that’s pretty much what the film amounts to for me—nice, pretty British people love each other and spin happily.

One Response to Ranking the 2015 Best Picture Nominees